Business

‘Indio-genius’: Geographical Indications as Intellectual Property for Indigenous People

"Indigenous peoples have a growing potential to transform their rich heritage into valuable intellectual property assets, specifically through geographical indications or GIs"

“Sir, maprotektahan ba nimo produkto namin?” (Sir, can you protect our product?) asked a coffee farmer during my visit to Bansalan, Davao in 2022.

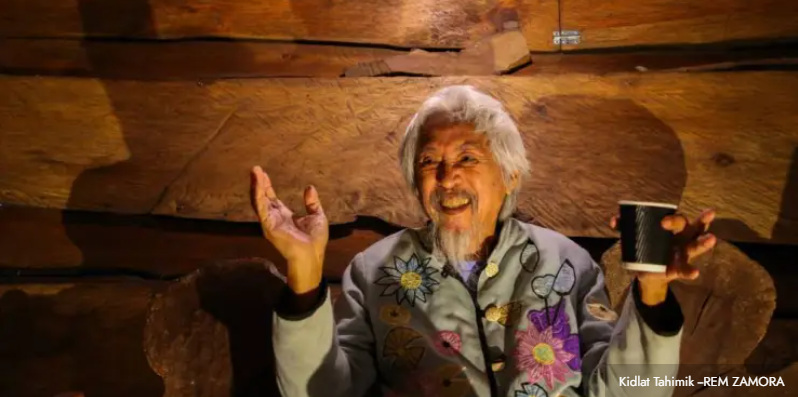

In one video of National Artist for Film Kidlat Tahimik, he emphasized calling Indigenous Peoples as “Indio-genius.” Indigenous peoples (IPs) in the Philippines are known for their deep-rooted traditions, customs, and cultural heritage, passed down through generations of storytellers. These highly traditional practices connect them to their ancestral past and sustain their communities’ way of life. The Philippines’ Indigenous Peoples Rights Act of 1997 says that they have continuously lived as an organized community on communally bounded and defined territory.

However, as poverty and climate change challenge their survival, IPs have a growing potential to transform their rich heritage into valuable intellectual property (IP) assets, specifically through geographical indications (GIs). This potential is seen in the experiences of indigenous communities engaged in agriculture, particularly those assisted by Varacco, its Smart FARM initiative, and its partners from UPLB, as well as the Flores and Ofrin Law Firm.

Indigenous knowledge as intellectual property

Indigenous traditions have always been a form of intellectual property, though rarely formalized. These traditions, whether agricultural methods, storytelling, or unique crafts, form a body of knowledge developed through experience and cultural practices.

For instance, the rich tradition of coffee farming in regions like Benguet and Kalinga, where unique coffee beans are cultivated, could be registered under geographical indications. This would protect not only the coffee but the specific methods and environmental conditions that contribute to the beans’ distinct flavor and quality.

Additionally, traditional crafts like T’nalak, the handwoven fabric made by the T’boli people, could also be protected under GIs, ensuring that its cultural and artistic value remains with its Indigenous creators. By registering these products and techniques as geographical indications, indigenous communities can take ownership of their traditional practices and preserve them for future generations. This formalization can turn their knowledge into legally protected assets, safeguarding their traditions from exploitation.

Protecting cultural heritage

Indigenous communities face external pressures from poverty and climate change, which threaten their cultural heritage and livelihoods. Traditional crops such as coffee and cacao, commonly cultivated by IPs, are vulnerable to environmental changes such as drastic typhoons. Registering these products under GIs helps ensure that IPs can continue to benefit economically from their traditional knowledge while protecting it from exploitation. This process also enables communities to develop resilience by securing legal protections for their products and methods.

Tools for economic empowerment

Registering indigenous knowledge under geographical indications enables communities to control their economic future. Coffee, cacao, and other agricultural products can be protected as IP assets, ensuring that any commercial use benefits the community.

For instance, by protecting T’nalak as a geographical indicator, the T’boli people can prevent unauthorized imitation and ensure that they are properly credited and compensated for the use of their designs. By formalizing these traditional practices, IPs can secure both cultural preservation and economic development. GIs offer IPs a pathway to protect their techniques for growing, harvesting, and processing crops, ensuring that the community directly benefits from the commercial value of their knowledge.

IP registration process

According to Flores and Ofrin Law Office, “intellectual property is not just a goal but a process.” It’s about recognizing traditional knowledge’s value, formalizing it through registration, and using it to build sustainable enterprises. For indigenous peoples, the process of IP registration is a way to take ownership of their culture and knowledge, ensuring it is passed on and benefits their communities economically. By formalizing their IP, they can control how their cultural heritage is used, preventing others from exploiting their knowledge for profit without fair compensation.

Raising living standards

The Intellectual Property Code of the Philippines (IP Code) recognizes Geographical Indications (GI) as an intellectual property. The Intellectual Property Office of the Philippines (IPOPHL) defines Geographical Indication as any indication that identifies a good as originating in a territory, region, or locality, where a given quality, reputation, or other characteristic of the good is essentially attributable to its geographical origin and/or human factors.

Registering geographical indications offers indigenous communities legal protection against the unauthorized use of their traditional practices. This allows them to license their IP, creating new revenue streams that can be reinvested into the community.

Such efforts also open up opportunities for sustainable enterprise development, focusing on preserving indigenous methods’ cultural significance. Beyond agricultural products like coffee and cacao, GIs can extend to crafts, medicines, and cultural expressions, offering broader protection for indigenous traditions.

Last October 2022, I attended the Asia-Pacific Symposium on Agrifood Systems Transformation in Bangkok, Thailand. Geographical Indications was a hot topic.

Play Video

The One Country One Priority Product (OCOP) initiative, launched by FAO in 2021, aims for the sustainable development of unique, culturally significant products. These include items with geographic indications, distinct farming practices, or heritage value.

OCOP fosters inclusive value chains to transform food systems in line with the SDGs. In May 2022, FAO’s Asia-Pacific Regional Office launched the regional OCOP, gathering ministers and officials to discuss implementation. The creation of a Regional Knowledge Platform was recommended to enhance collaboration. OCOP’s success relies on strong government leadership and active stakeholder participation to ensure country ownership and sustainability.

Enterprise development and sustainability

Building sustainable IP-based enterprises is not just about creating commercial ventures — it is a means of preserving cultural heritage. By registering their traditional practices, indigenous peoples can increase the value of their enterprises and protect their knowledge from exploitation. The registration of GIs allows indigenous communities to retain ownership of their brand and its traditions, creating powerful tools for economic growth and cultural preservation.

From indigenous to “indio-genius” peoples in the Philippines, supported by organizations like Varacco, Thinnkfarm, or Flores & Ofrin Law Firm, can leverage their traditional knowledge as intellectual property to create sustainable, IP-registered enterprises. By formalizing their agricultural and cultural practices as IP, they can protect their heritage, increase their economic value, and preserve their traditions for future generations. Intellectual property, when embraced as a process, offers a pathway to both cultural preservation and economic empowerment.

photo credits: traveltrilogy.com for the Tinalak festival, Rem Zamora of the DI for Mr. Kidlat Tahimik's picture

About the Author

Aries Asilo 2006

Ariestelo Asilo of Batangas, Philippines, started working at the age of six by selling sweepstakes tickets to make ends meet. He finished BS Nutrition and Master of Business Management at the University of the Philippines through the scholarship of US Peace Corps Alumni Foundation for Philippine Development. He worked for a UNICEF project on Anemia at UPLB and eventually taught food courses in college at the age of 21. Aries pioneers nutrition entrepreneurship through coffee production and research, and foodservice management. His interest in coffee started in 2012 when he saw coffee beans just scattered in the mountains of Lobo, Batangas. He co-wrote the feasibility study for Lobo’s Farm to Market Road that won a grant from World Bank to create an 8-km road benefitting 9,000 people of Lobo. He is the CEO and Co-founder of Varacco Inc., that focuses on coffee as a global commodity and a Filipino heritage icon. His goal on nutripreneurship is sustainable foodservice systems by progressive value addition leading to an increased productivity, profitability, and product quality. He is Speaker for both national and international conferences for his innovative model on Nutripreneurship. In January, 2020, Aries was selected as one of the 4 Filipinos who was awarded the Young Southeast Asian Leader Professional Fellow for Economic Empowerment by the American Councils for International Education and US Department of State. Asilo is 2020 UPLB Distinguished Alumnus for Nutrition Entrepreneurship and Community Nutrition. In 2021, Aries won a grant from ACDI-VOCA for his coffee research funded by USDA. His company Varacco also won as one of the 50 United Nations’ Best Small Business: Good Food for All out of 2,000 companies from 135 countries, given by United Nations Foods Systems Summit 2021 held in July, 2021. He also won as the winner of Conservation Optimist Southeast Asia Awards for Climate given by Eastwest Center USA. He is also one of the Swedish Institute Management Asia Fellows sponsored by the Swedish government. And finally, he is recognized as the The Outstanding Young Men Honoree for Social Entrepreneurship 2021 in the Philippines. (Source: LinkedIn)