Opinion

Ninoy Aquino '50 Week: Marcial Bonifacio - Filipino, An Upsilonian by Jose Ampeso '68

This week, the Upsilon Sigma Phi pays tribute to hero and martyr, fellow Benigno "Ninoy" S. Aquino, Jr. '50 (November 27, 1932 - August 21, 1983) on the occasion of his 40th death anniversary.

This is the last article in the series and was first published in "We Gather Light to Scatter: Ninety Years of Upsilon Sigma Phi" in 2009. It tells of Mr. Ampeso's personal encounters with the late senator as a young brod in the Upsilon Sigma Phi, and his stirring account of how he agonized over Ninoy's plea for assistance in securing a Philippine passport that allowed Ninoy to return to the country. It was Mr. Ampeso who was then the Vice Consul at the Philippine Consulate in New Orleans who helped issue two passports to the late senator, one in his real name and the other under an assumed name, Marcial Bonifacio.

Ninoy Aquino week: Marcial Bonifacio - Filipino, An Upsilonian

by Jose Ampeso '68

"To many Filipinos, Ninoy Aquino's assassination in in August of 1983 was a very tragic incident. The dreadful loss of his life was truly a supreme sacrifice he paid! It marked the beginning of the end of Ferdinand Marcos' hedonistic rule that did not fit within the bounds of democratic processes.

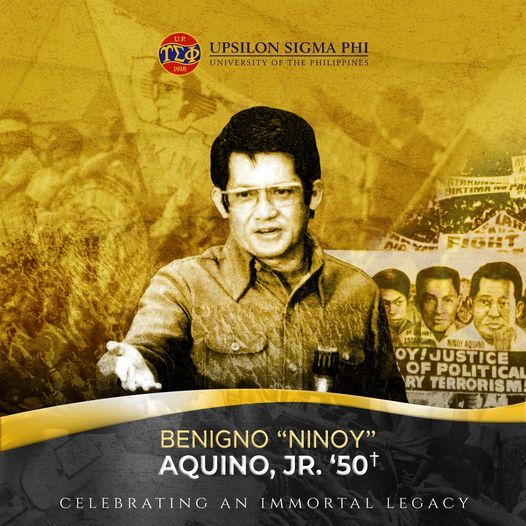

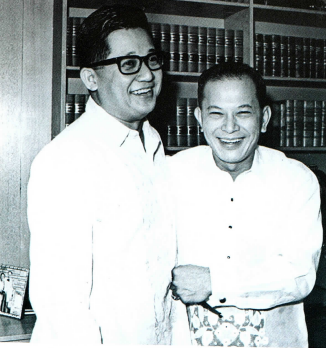

Senators Ninoy Aquino '50 and Doy Laurel '47

My personal estimation of Ninoy was that of a youthful maverick and ambitious journalist turned politician of post WWII vintage, among other brilliant colleagues of his time. For sure, he was the new player on the block, one in a hurry, from governor of Tarlac in 1963, he ran for the Senate and won in 1967, the sole candidate from the opposition ranks, while the other seven successful ones were from among the Marcos administration! Indeed, he could not bide his time in going up against a sitting president who had great ideas of his own! Marcos was a veritable tactician and veteran political leader, a law scholar and bar topnotcher who underwent the rigors of WWII, and struggled himself towards the top of Philippine politics, the only one to have won the presidency twice! This tussle between Ninoy and Ferdie (or Andy), who in their U.P. student days both joined the Upsilon Sigma Phi fraternity, led to, for the former, a heroic death but for the latter, an eventual exile and rejection.

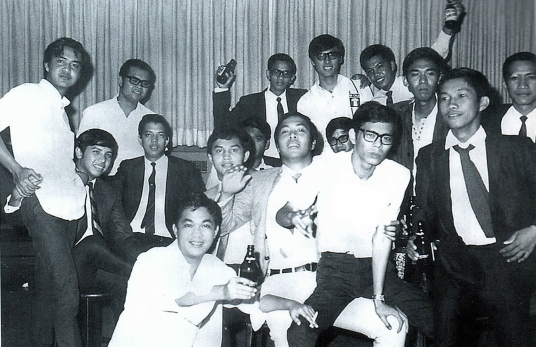

Upsilonians, 1969, at front, standing on extreme right, is Joey Ampeso '68.

Among the fifty-three lucky neophytes to successfully make it the 1968 initiations of the Upsilon sigma Phi, thirty-one from U.P. Diliman and twenty-two from U.P. Los Baños, I too struggled and survived the severities of initiation, our batch rightly called "the golden batch," half a century after the fraternity's founding in 1918. Both these two national stalwarts, fellows Ferdinand E. Marcos and Benigno S. Aquino, Jr., suffered from their own initiations, respectively in 1937 and 1950, to be able to join the U.P.'s first and Asia's oldest Greek-lettered fraternity. I regarded both, among a few, as "tried and true." There are many stories, within or outside the fraternity, that will prove this honored appellation.

A Maverick Politician

Two or three weeks old in the fraternity, I was asked by the fellow Custodian (the resident fraternity finance officer whose name escapes me) to help him solicit funds for the fraternity from well-off senior alumni brods, especially in the Senate. There, we got ourselves busy hustling for donations from the brods. Fellows Turing Tolentino '31, Gil Puyat (honorary fellow), Doy Laurel '47, Gerry Roxas '46 and Ninoy Aquino '50. Having been done with the first four, we approached brod Ninoy who instantly inquired how much the others gave. Before the fellow Custodian could open his mouth, I blurted out "one-thousand pesos, senior brod." He looked at me as if to question whether indeed, they each gave out such an amount, which was surely huge in those times. Then he said, "brod, you must be a new brod, mukhang na-initiate ka ng husto (you must have been clobbered during your initiation)!" "You just wait awhile brods, I do not have enough cash here," he said, He then signaled for some money from one of his staff, I believe it was the late Raul Roco, and gave us one-thousand pesos. Actually, the four other senators gave a total of one-thousand and Ninoy himself donated the same amount notwithstanding reports of him being a scrooge. At any rate, I somehow felt this incident was the start of a mutually amiable and fraternal association with a senior brod - on the rise, a maverick in his own right, a politician extraordinaire.

Grand Yunost

In December 1969, the fraternity presented with great pride, the Grand Yunost, a ballet and circus group from the Soviet Union composed of youth performers from Kiev. Single-handedly, the resident chapter brought this group from far-away Russia to perform not only in Manila, but also to several cities in the south, to the delight of the crowds.

Yunost youth folk dance company performing a Ukrainian dance, 1970's stock photo.

Requested by the resident brods to tender a dinner for the Grand Yunost troupe, Ninoy who traveled early on to Soviet Russia, was a gracious host during the bamboo-lit dinner at his residence in Quezon City. The neophyte senator, noticing that I spoke some Russian, asked me how I learned the language. I candidly explained that because of the fraternity's planned cultural undertaking of which he was now part of as the dinner's host, I took it upon myself to take up Russian lessons under the tutelage of Professor Zeus Salazar's wife.

My fraternal connection with Ninoy would be enhanced through our two fraternity brothers, Roquito Ablan and the late Nering Andolong, all three belonging to Upsilon Sigma Phi batch 1950. As a new Upsilonian, and in my youthful exuberance, I was slowly and steadily warming up to Ninoy to earn his friendship, initially, fraternal and later on, personal. At the same time though, I had my own encounters with the other big brod, the late Ferdinand E. Marcos '37, but that's for another story.

Nurtured Association

It was at his memorable Quezon City residence at Times Street (he used to work for the Manila Times newspaper) where I visited with and last saw Ninoy sometime between his prison release and eventual exile to the United States in 1979, the year I made it to the Foreign Service Officers' (FSO) exams, the entrance into the officer group of the Department of Foreign Affairs. I did not know that our paths would cross again in the United States where my association with Ninoy was nurtured further. It was to the southern port city of New Orleans that I, in the spring of 1982, I was posted as Vice-Consul.

Among the very first friends I made during my New Orleans tour of duty was a Filipino graduate student who happened to be Ninoy's cousin, a cousin-in-law to be exact. Through this cousin cum intermediary, the exiled senator in Massachusetts, found out about my assignment to the Philippine Consulate General in New Orleans. I would remember Ninoy, a voracious reader of history, as having urged me to take up advanced studies at Tulane University, specializing in African-American studies. I really did not get the chance to do so as graduate studies were financially prohibitive, especially at the top university of the south.

The 1982 U.S. State Visit

Over a month before President Marcos' state visit to the United States in September of 1982, I was ordered to report to the Philippine embassy on Washington, D.C. to assist with the preparations. A week before the event, I heard that Ninoy was also in Washington, having tete-en-tete conversations with his journalist-friends and former colleagues who were there to cover the state visit. Days before Marcos' arrival, these journalists stayed away from Ninoy while he was doing the rounds of the coffee shops near the embassy. They literally disappeared, avoiding Ninoy like the plague. I sensed some immediate advisory must have been given to these Filipino newsmen to stay away from if not ignore Ninoy who, in the meantime, tried to touch base with me. I was just too busy for even a moment with my senior brod, who conveyed his understanding of my earlier situation in one of our later exchanges.

Ninoy with brods raising the Philippine flag in Boston sometime in the third quarter of 1981. L-R, Jing Yuvienco '62, Del Sta. Ana '63 (+), Ninoy '50, Danny Mangunay '65 and Oli Tuico '58

After the state visit, I gathered that a get-together was held among the brods from New York and Massachusetts at Ninoy's residence near Boston. According to a few brods, Ninoy asked about me. On more than one occasion, Ninoy would communicate with me to say hello and asking that we meet up, if possible, and usually, at some U.S. airport, as he was going to this or that place through the said airport. What I gathered from him during these casual meetings was his eagerness to return to the Philippines, to return to the Filipino people - sooner rather than later! I knew very well that he was in touch with a thousand and one other people who would have a thousand and one things to pass on to him. How all of these got processed in Ninoy's brain, only he could possibly know.

"I Need a Passport"

Sometime early in 1983, I learned from several sources and from Philippine newspaper accounts, that Ninoy was dead serious in returning home, and that various authorities in the Philippines were already planning deliberate moves in reaction to this calculated move by Ninoy, taking into account the crucial factor of Marcos' faltering health. This meant that the latter was not in full control. Meantime, despite mv being in New Orleans, I became very much involved with the issue.

Ninoy called me up in New Orleans one early one morning, saying "Brod, help me. I need a passport. I need to travel outside the United States and I request your help, please." My immediate reaction was, "Senior Brod, I will act on your request. But could you somehow

inform Brod Roque (Roquito Ablan) about this matter?"

For the next week or so, I was consumed by the many questions Ninoy's extraordinary request triggered in me. Should I or shouldn't I? Why or why not? What could I do and how could I do it? My dilemma was made worse because I could not talk it out with anyone, as I had to recognize and appreciate the situation of the government then. Although martial law was lifted in 1981, it was but in name only - the police powers of Big Brother were still in place, not only in the Philippines but more so in Philippine foreign diplomatic and consular establishments. There was always some eye or ear in each post, especially those in the United Sates.

While I was fully sympathetic with Ninoy's wanting a passport, I felt that whatever response I would make would bear grave implications, primarily on my side as a civil servant, a brod and a person. Selfishly or selflessly, I told myself to act according to my conscience and my fidelity to the civil service.

Ninoy called back after a few days, to reiterate his request for help but I still had to hear from Roquito. When Roquito finally rang me up, he told me, "You can issue the passport to Ninoy. I had it cleared upstairs." I asked him, "Manong, upstairs is upstairs. How about (the people) down below, especially the military?" Himself aware of the state of affairs then, he responded in Ilocano, "Why, is there a military person or representative assigned over there who would report here?" I said "Adda!" - Ilocano for "there is." He understood my concern so he advised me to be extremely cautious, reiterating that Ninoy's passport can now be positively acted upon.

A week later, I met up with Ninoy and handed over to him two passports, one in his name and the other, with his nome de guerre, "Marcial Bonifacio." Ninoy expressed his gratitude saying, "Brod, I truly appreciate your kind and brave act. I shall see you in Manila."

That was in mid-spring of 1983 when we last met. The next time I heard from him was in early August of 1983, when he called to confirm that he was set to return to the Philippines and that I should see him when I get back there.

Past midnight of August 21, I was driving along Interstate 5 on my way home after attending a couple of community functions in the city of jazz. I was listening to some Cajun music on the radio when suddenly the music was interrupted with a breaking news item: "Ninoy Aquino, Philippine opposition leader, was shot upon arrival at the Manila International Airport. It could not be determined if the shooting was fatal."

I couldn't believe what I just heard! Driving home as fast as I could, I immediately got on the phone to call Manila. That he was shot was confirmed, and hours later, his death was likewise confirmed.

Ninoy's lifeless body lies on the tarmac at the Manila International Airport after he was shot while being escorted out of the airplane by security forces on August 21, 1983.

I could not hold back my tears even as I began to speculate on the implications of his death, to the country and to the Filipino people. I immediately sensed that there could be some serious investigation of Ninoy's killing, including how he managed to get a Philippine passport. I could foresee that Ninoy's senseless loss would somehow unite the Philippine opposition against President Marcos, upon whom full blame for Ninoy's reprehensible death would be squarely laid.

Sleepless in New Orleans

For the next month, I had to act at work as if nothing happened. I was informed that all diplomatic posts the world over were ordered to check out their consular records to verify where Ninoy's passport came from. My post in New Orleans was no exception. However, no trace whatsoever could point to New Orleans as the source. During the month-long investigation of the post's consular records, I must admit that I had sleepless nights. I even contemplated the extreme of committing hara kiri, a foolish though! I thought about going on leave, but that was even more foolish as it was only going to draw unwarranted attention. What I eventually did was to behave as normally as possible. I spent most evenings with Filipino community leaders or with some American neighbors, to while the time away.

Cherished Memory of Ninoy

It is over a quarter century since Ninoy was shot at the tarmac of the airport that has been renamed in his honor. His aspirations for the country and its people still remain aspirations to be achieved. Monuments, statues, a national holiday - these and many other attributes to him have been set to give recognition to this "dreamer" who asserted that "the Filipino can."

I take pride in having known a man, a brod, who believed that "the Filipino is worth dying for."

Ninoy's words of appreciation and his promise that he would see me in Manila lingers in my mind. My greatest dream then was to meet him again in the home country upon his return, but destiny dictated otherwise."