Opinion

Ninoy Aquino '50 Week: Ninoy in Exile by Rogie Concepcion '66

This week, the Upsilon Sigma Phi pays tribute to hero and martyr, fellow Benigno "Ninoy" S. Aquino, Jr. '50 (November 27, 1932 - August 21, 1983) on the occasion of his 40th death anniversary. The Upsilon Sun will be reprinting articles about him and tributes to him written by his fellow Upsilonians.

Below is an excerpt taken from Chapter Four of "Un Memoire Petite," the personal memoir of fellow Rogie Concepcion '66; it tells the story of Ninoy's life in exile in the United States.

A country that could have been. A vision lost. Remembering Ninoy Aquino

(Part 2 of 3)

NINOY IN EXILE: Political Activism

Sometime in 1980, Ninoy had a heart attack and was released to undergo a triple bypass heart operation in the United States.

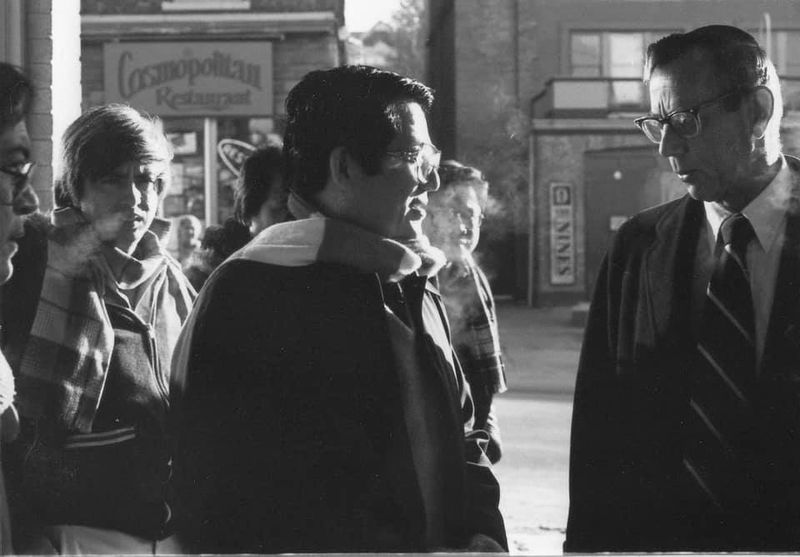

After his recovery, he was offered a fellowship at Harvard’s Center for International Affairs in Boston. In 1981, a meeting with Ninoy was arranged by an intermediary for us to meet with him at Cornell University where he was scheduled to give a talk.

Cornell University 6:30 AM in the morning with Ninoy before his talk. From left flanking Ninoy: Tony Cruz ‘64, Vic Cruz who replaced Ruben Cusipag (+) ‘57 as editor, Jimmy Borres (+) ‘63, Rogie Concepcion ‘66, Eddie Lee (+) ‘53. Noel Cruz ‘66 was taking the photo.

We - Jimmy Borres, Eddie Lee, Tony Cruz, Noli Cruz and I, who belong to the same fraternity at the University of the Philippines, Upsilon Sigma Phi, and involved in the Toronto newspaper Atin Ito, drove to Cornell at midnight. We arrived at Ninoy's hotel at 3:00 a.m. and knocked on his door.

We drove from Toronto at midnight and arrived at around 3:00 p.m. at Ninoy’s hotel. My old station wagon was driven by Momong who had introduced himself as one of Ninoy’s bodyguards and driver. Camera shy, Momong popped up one day to ask if we wanted him to arrange a meeting with Ninoy. As mysteriously as he appeared, he disappeared as quickly. We never saw him again after that meeting.

Ninoy was apprehensive when he opened the door but quickly warmed up when he found out we were brods. I would never forget that morning. From 3;00 p.m. to 7:00 a.m., before his scheduled lecture, as we listened to him. He was an unstoppable force. He spoke clearly about his vision for the country. I was transfixed and was convinced that he was the “messiah” that the country badly needed, languishing under martial law's corrupt aftermath.

Noel Cruz ‘66 in the background just to the right of Ninoy. I don’t remember if the person Ninoy was speaking with was an academic from Cornell or security detailed to him.

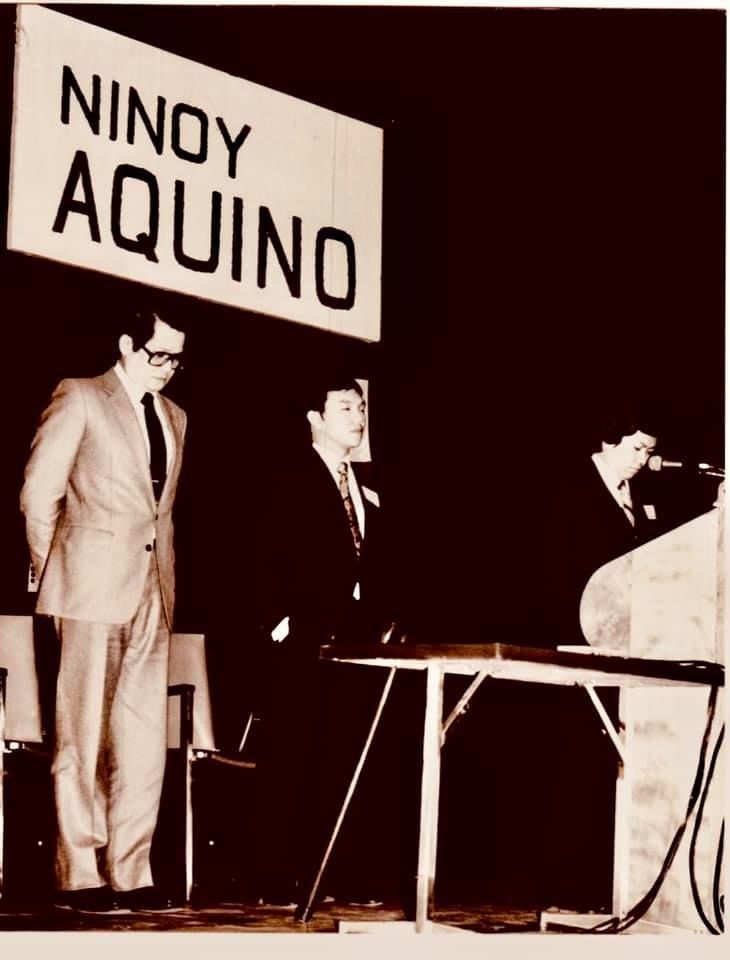

After that Cornell meeting in 1981, I became reacquainted once again with Ninoy. We brought him to Toronto to give a talk to the Filipino community in a symposium and arranged for widespread news coverage with leading Canadian newspapers, television and radio.

We organized a symposium for Ninoy in Toronto.

Tess and I would visit Ninoy and Cory several times in Boston where I would meet many other prominent Filipino politicians who were also visiting. Cory was not generally involved in these political conversations, but I could tell that she was clearly his closest confidant on political matters. Tess would help Cory shop while we would meet.

One politician I will not forget meeting at his home in Cambridge was former Senator Ernie Maceda, who was once a former Marcos presidential spokesman. Maceda was proud of showing off, pointed at his double thumb denoting that it was an auspicious sign, and destined him to achieve greater heights. I thought he was sleazy and could not be trusted, and I suspected a likely double agent acting for the Marcos regime.

A grass roots movement for the termination of martial law started with these meetings, to apply international pressure and push Marcos to lift martial law by exposing the abuses and corruption of the regime. I became involved.

I would continue to have conversations with Ninoy until the evening before he was assassinated. He confided that he had regular conversations with brod Marcos. That night, learning that he was flying to Manila, I spoke with him over the telephone a few hours before his flight. I asked why he was returning home. I thought this to be extremely dangerous, given that he was considered a serious threat to the Marcos regime.

Ninoy said that his informants inside the regime informed him that Marcos was extremely ill and may not survive. He felt that he had to be there when it happened at “siguradong magkakagulo” (chaos will ensue). I asked Ninoy, do you not fear for your life? His reply is now indelibly seared in my brain; “I would rather die a martyr than an inglorious death run over by a car”.

We had an overnight vigil with friends and supporters in our Mississauga home waiting for word of his trip home.

Ninoy miscalculated the brazenness of the regime’s response believing that as he was surrounded by a plane full of international journalists, he would surely be protected from any serious harm. He was wrong and the rest is history now.

That day was a turning point for me. I was angry. With the callous manner of Ninoy’s death, I had no choice but to be involved. I became a part of the anti-martial law movement that spread like wildfire in North America, calling for the toppling of the regime.

I was interviewed on Canadian television and quoted in newspapers about the heinous assassination of Ninoy. I resigned from Atin Ito newspaper that I was partly instrumental in setting up and along with two other writers, a former editor of the Manila Chronicle and an ex-Manila Bulletin journalist, set up a newsletter that we called Aquino.

I had many conversations with Senator Jovito Salonga. He was then still carrying shrapnel in his body as a result of the bombing in Plaza Miranda. An intellectual, decent and honest, I did not, however, think he was presidential material.

I met many Filipino political personalities during the period of ferment, who visited us in Toronto including Senator Jovy Salonga and his wife Lydia, who stayed several times with Tess and I in our Mississauga home, activist filmmaker Lino Brocka, Jimmy Laya, who had served as Budget Minister and Central Bank Governor under the Marcos regime, and Senator Raul Manglapus.

There have been many accounts of the curious relationship Ninoy Aquino had with Marcos. This is now a footnote in Philippine history, but I had a first-hand glimpse of this and had written about it in another chat group. This is what I said when the question was raised about the relationship between Aquino and Marcos:

I was privileged to have had a glimpse of this. Although Ninoy and Ferdie (Marcos) were fierce political and formidable foes, Ninoy intimated that he had continuous conversations with Ferdie even when he was incarcerated and after he was released and exiled. They would address each other as brod. They never lost their respect for one another.

On the eve of his departure for Manila on that ill-fated day he was martyred, I spoke to Ninoy. He knew it was extremely risky, but he was compelled to go as it was his duty.

His concern was the failing health of Marcos. His inside sources predicted then the imminent demise of the president, and he feared that the country could collapse into chaos. He had to be there to rally the opposition.

By surrounding himself with international media, he gambled that he would be unharmed, although he was ready for the worst and willing to take the supreme sacrifice. He miscalculated, but also won at the end.

Although I think he would not have blamed Marcos for the brutality of his assassination or for his death.

By the way that Ninoy talked about Marcos, you would think that they were good “friends”. They certainly considered each other as brods, and not outwardly hostile to one another.”

A Curious Brotherhood: A footnote to the turbulent Philippine history of the 1980s, while my memory still remains intact.

During my personal conversations with fraternity Brod Ninoy, he related several times his continuing dialogue with Ferdie. They were playing an intriguing form of power chess.

Yet, I did not sense any animosity or bitterness on Ninoy’s part nor did he indicate any on Ferdie’s part either when Ninoy talked about his interactions with Macoy.

It was fascinating and intriguing to watch both protagonists play a dominant role and whose legacy was to and still dominate Philippine politics for 5 decades.

And they were members of small fraternity that came out of my alma mater - the Upsilon Sigma Phi.

Rogelio J. "Rogie" Concepcion '66 is a retired investment and corporate banker with the Royal Bank of Canada, a community leader and activist who helped found "Atin Ito," a widely-circulated Filipino community newspaper in Ontario, Canada; he and his wife Tess now own and operate several bed and breakfasts in the Toronto metropolitan area.