Opinion

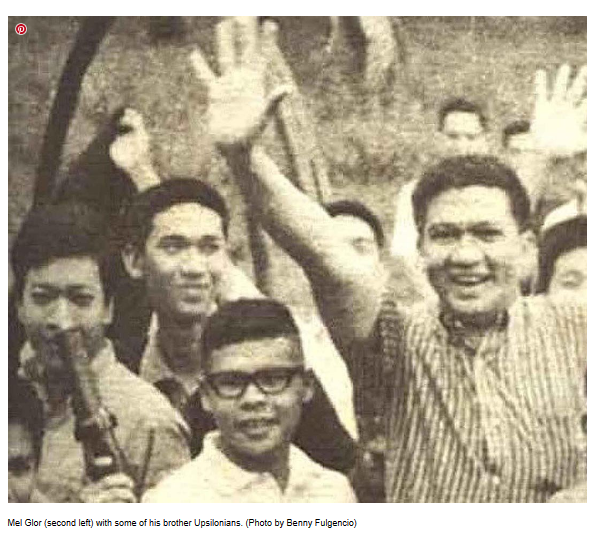

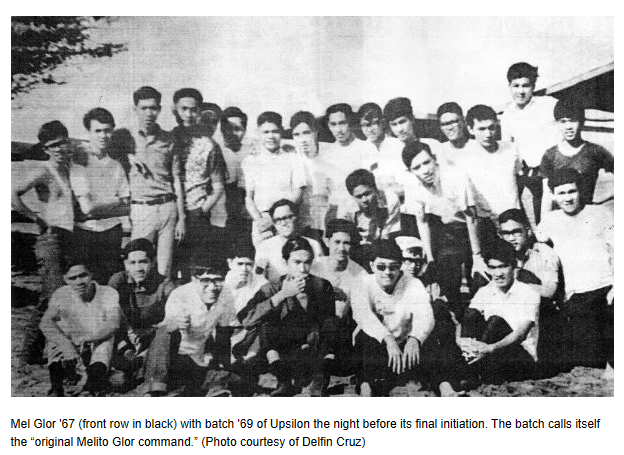

Remembering a Fraternity Brod Named Melito by Raul Palabrica '67

The invitation of a 78-year old mother to her son's fraternity batchmates (1967, Upsilon Sigma Phi) to visit her in Atimonan, Quezon, came as a surprise.

Two Sunday's ago, I, together with four other brods, drove to Atimonan, for a sentimental reunion with the mother of a batchmate who willingly gave up his life for the principles he believed in.

Twenty-two years after the death of Melito Glor, Inang Gloria is still at a loss on why her child abandoned what could have been a comfortable life of a medical practitioner in favor of the leftist underground movement.

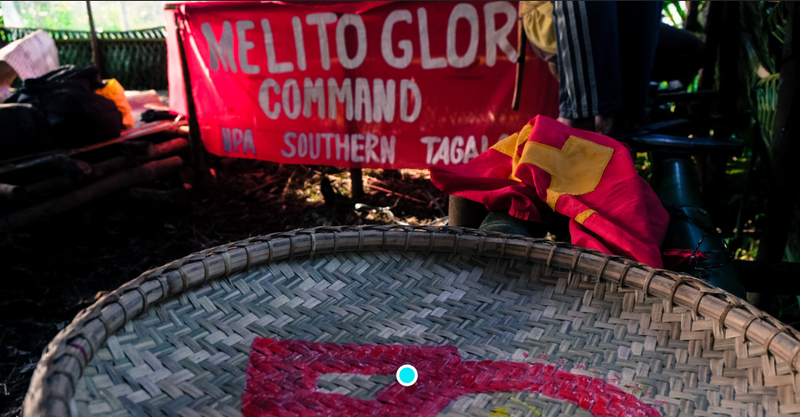

Melito Glor is the man in whose honor is named the biggest and most active armed group of the New People's Army. The Melito Glor Command operates in the mountain fringes of Laguna, Batangas and Quezon provinces.

The NPA command has, for more than a year, in its custody, Army Major Noel Buan and PNP Chief Inspector Abelardo Martin of Dolores, Quezon. Negotiations for their release have bogged down due to differences in the procedures to be observed in setting them free.

The two-story house Inang Gloria lives in showed signs of old luxury. It had the conveniences of modern living, confirming the upper class standing of their family.

Tears fell from her eyes when we recounted the good times we had with her son inside and outside the U.P. campus. She asked us why her son did not concentrate on finishing his medical studies instead of joining the leftist movement.

Shortly after the declaration of martial law in 1972, Melito, then a student of the College of Medicine of the University of the Philippines, gave up his studies to join the NPA in its armed struggle against the Marcos dictatorship.

Carrying the nom de guerre "Commander Haba" probably due to his lank 5'10 body frame, he rose from the ranks to become one of the top leaders of the leftist armed front.

He was killed in a firefight with government troops in 1978 in Calauag, Quezon. According to NPA insiders, he fought it out with the soldiers to cover his men's retreat when they were cornered in a hut. He was 30 years old.

Inang Gloria mused that had her son's life taken a different turn, Melito would have been a successful professional like his batch mates.

In spite of the 22 years that have passed since his death, it was obvious Inang Gloria was still in pain over the loss of her only child.

STUBBORN

Inang Gloria was quick to add that she expected the turn of events in her son's life. He was stubborn. When he sets his mind on something, he will do everything to get what he wants. His deep commitment to the leftist movement reflected his character.

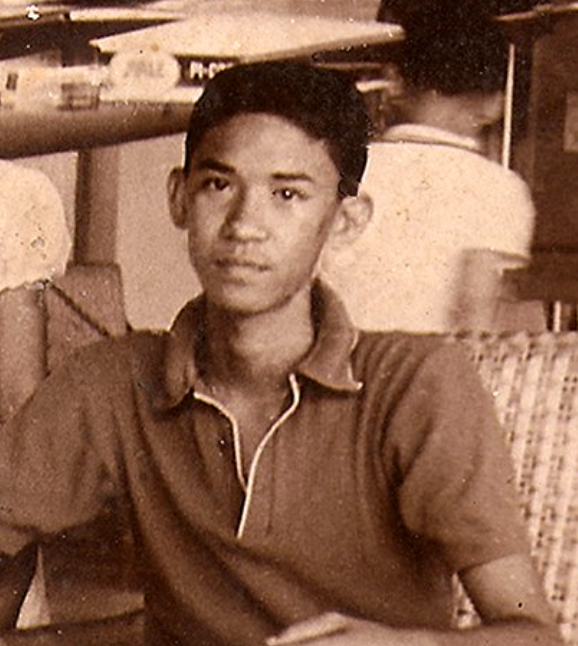

Browsing through the yearbook of the Quezon Memorial High School where Melito graduated in 1965 as salutatorian, the notes written under his photo described him as "Campus James Dean" whose ambition was to enroll in the Philippine Military Academy.

Apparently, during his high school years, he entertained thoughts of joining the military service. The irony of the plan and the fate he suffered in the hands of government troops was not lost on us.

MARRIAGE

Over snacks of native delicacies, we reminisced on the wedding of Melito to a female comrade in 1973. The ceremony was held at a Catholic church in Cuba, Quezon City, with scores of student activists- and military intelligence agents - in attendance.

Shortly after the wedding, the newly wed couple went back to the mountains to resume the armed struggle against the Marcos dictatorship.

Out of that union was born a son who was to die of natural causes before he was a year old. Melito's widow later rejoined the mainstream of society and remarried.

According to Inang Gloria, she did not at first believe that his son had been killed in a firefight with government soldiers. There were no eyewitnesses who could confirm his death.

There was even talk among the barrio folk near the area where the firefight happened that Melito was able to escape the pursing soldiers.

DREAM

Inang Gloria only accepted her son's death weeks later when she dreamt of him wearing a long-sleeved white shirt and khaki pants waving goodbye to her as he was about to board an airplane.

She took that dream as a message from her son that he was indeed gone forever.

With that in mind, she and her husband trekked to Calauag to visit his reported burial site. They requested the exhumation of his remains so that they can be interred at the Atimonan cemetery.

Authorities turned down the couple's request. The parish priest also cautioned them agains forcing the issue, as the times then were dangerous. He suggested that the couple retun after five years to ask for their son's remains.

In 1983, Melito's parents made a go for it again. This time, the authorities relented. The gravesite revealed only bones and tattered clothes.

Inang Gloria's maternal instinct, however, told her that the bones were those of her son' She recognized the pair of pants he was buried in was the same one he wore when he got married.

After the traditional church blessings, Melito's bones were brought to Atimonan for final interment at the town cemetery.

Sometime in 1986, a movie producer offered to make a film about Melito's life. After consultations with Melito's former wife, however, Inang Gloria and her husband decided to turn it down.

They did not want their son's memory reduced to a commercial venture. Melito's father died in 1993.

GOODBYE

It was late in the afternoon when we said goodbye to Inang Gloria.

Holding back her tears, she said she was happy we still remembered her son after all these years. We left her mementos that would remind her of the good times her son had at U.P..

From the way she waved us off, we felt that she was proud of what her son did and died for.

Editor's Note: This article was first published in the front page of the Philippine Daily Inquirer in September 24, 2000.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Raul J. Palabrica is a lawyer, columnist and business executive who serves as Chairman and Publisher of Philippine Daily Inquirer, Inc.. He graduated from the University of the Philippines and served over ten years as legal counsel of the Inquirer. He has been a columnist for the Opinion and Business sections of the paper for over three decades. Mr. Palabrica also served as Commissioner of the Securities and Exhange Commission (SEC) of the Philippines.