Opinion

The Fraternity Fez and Cane by Victor Avecilla '79

The Fraternity Fez and Cane

by VICTOR C. AVECILLA '79

When the organizers were making preparations for Balik Tambayan: Fifty Years of Batches '73 and '74 scheduled on January 20, 2024 at the UP Ang Bahay ng Alumni, they included a "Fez and Cane" segment to highlight the event.

This essay prequels the event with concepts and origins that our founders harnessed more than a century ago to institute the first fraterniy of the Philippines. Thanks to our frat historian, Professor Chito Avecilla.

Foreword by Tom Firme ‘74

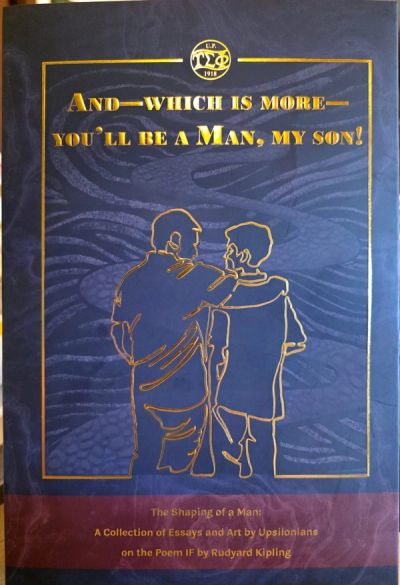

The 2023 Upsilon Sigma Phi Fellowship Council of U.P. Diliman wearing traditional barong and fez with the Illustrious Fellow holding the cane.

Members of the Upsilon Sigma Phi memorialize their being part of the fellowship by using fraternity paraphernalia often seen at formal gatherings.

The most visible of the Upsilonian's ceremonial paraphernalia is the fez (plural fezzes), a cone-shaped headgear made of red felt truncated to a rectangular shape and decorated with an adorning blue tassel. These two colors are based on the fraternity's official hues -- cardinal red and old blue.

In addition, the fraternity seal, reduced to a proportionate size, is sewn on the left front side (from the viewer’s perspective) of the fez, while the tassel dangles on the opposite side. Some pre-World War II vintage of the fraternity fez had the seal sewn on the right side, instead of the left. Most of the fezzes worn by contemporary Upsilonians have an embroidered fraternity seal for added elegance.

The fez is Middle Eastern in origin, and it was first used there, and in Eastern Europe, during the Byzantine era as well as during the Ottoman Empire. Originally, the fez came in two shapes, namely, the truncated cone described earlier, and a short cylindrical one made of kilim fabric. The early fezzes were dyed in red using Crimson berries.

It is named after the City of Fez, in Morocco, which was violently overran by Muslim zealots in the early part of the eighth century in their fight against the spread of Christianity in the region. After killing an estimated 50,000 Christians at Fez, the Muslims dipped their caps in the ensuing pools of blood visible everywhere. The blood-stained caps eventually came to be called fezzes.

The fez became an integral part of men's attire during the Ottoman Empire, and was also the most recognized indicator of Ottoman identity. Almost all of the notable personalities of the empire, and a large percentage of its male citizens, wore the fez in public.

In Arab countries that belonged to the Ottoman Empire, the fez was called tarboosh, an ancient Persian word that means "headcover."

While the fez was considered a symbol of religious adherence to Islam due to the carnage in the City of Fez, many Christians and Jews wore this headgear in public during the Ottoman Empire.

In 1925, President Mustafa Kemal Atatürk of Türkiye (the former state of Turkey) proclaimed his country a secular, rather than an Islamic state, and he outlawed the public use of the fez. Although it was still used in other countries, the eventually fez fell out of fashion in Europe and in some areas in the Middle East and is rarely seen in those places today.

Shriners International, an international brotherhood organized in the United States in the late part of the nineteenth century, adopted the fez as its official headgear in 1872. It represented the Arabian theme on which the brotherhood was founded. In addition, the fez serves as an outward symbol of membership in the brotherhood, much like the apron worn by Shriners during their formal ceremonies. All Shriners are Freemasons, but not all Freemasons are Shriners.

Because the formal rites of the Upsilon Sigma Phi were lifted in part by its Founders from the ceremonies of Freemasonry, and considering that all Shriners are Freemasons, the Founders adopted the Shriners' choice of the fez as the official headgear of the Upsilon.

When Upsilon Sigma Phi Batch 1949 celebrated its golden anniversary in 1999, a "gold" version of the fez was given to each of the jubilarians. It was the brainchild of the late Abelardo Villanueva 1949. Since then, issuing a gold fez to the golden jubilarians of the fellowship became standard practice among Upsilon alumni.

The gold fez came in various shades and hues, from the original bright and shiny type akin to a woman's purse, to the current subtle yellow made of flannel.

At the diamond anniversary party of Batch 1963 held in November 2023, the jubilarians were each issued a "diamond fez" made from a fabric with a bright shade of gray. It is almost colorless when viewed at certain angles during daylight hours, and it should be so, because a diamond often bears no particular color.

Another mainstay of every Upsilonian's ceremonial paraphernalia is the fraternity cane, which is brought to formal gatherings, particularly in investitures and initiation rites. The fraternity cane is made of strong wood, varnished, and tapers toward the end.

It was originally shaped as a candy cane so as to make it easy to hang over the forearm during attendance at important gatherings. Early tradition has it that each cane is custombuilt to suit the height of its owner.

The fraternity cane, formally referred to in the plural as "the canes of the fellowship," symbolizes nobility, since the cane was an integral part of the daily attire of respected gentlemen in Europe and the United States for a long period.

It also symbolizes authority and retribution. When pointed by an Upsilonian, particularly a dignitary, at "a poor blind beggar seeking admission to the fellowship," the cane ceremoniously suggests swift retribution from the beggar, when he is already a regular fellow, should he end up committing a breach of his sacred pledge to abide by the rules of the fellowship -- a pledge made at the time of his admission to the Upsilon.

The popular account that the tip of the fraternity cane hides a dagger belongs to the stuff urban legends are made of.

In the decades following World War II in the Philippines, the use of the cane as part of standard fraternity regalia was temporarily discontinued. Towards the later part of the century, however, a regained interest in the cane turned up among the resident fellows. Soon enough, the versions of the cane, varying in colors, shapes and handles, became readily available, and were distributed to jubilarians during annual reunions.

The practice of having a fraternity cane as part of the Upsilon ceremonial regalia was adopted from an American university brotherhood, the Phi Beta Sigma, which was founded in 1914 at Howard University, a federally chartered historically black-dominated institution established in Washington, D.C.

About the author:

ATTY. VICTOR C. AVECILLA '79 is a Professor of the Broadcast Communication Department of the University of the Philippines, College of Mass Communication. He obtained his Bachelor of Arts (Broadcast Communication), Bachelor of Laws and Master of Arts degrees from U.P. Atty. Avecilla specializes in Media History, Media Ethics and Media Law. Mr. Avecilla was a former editor in chief of the Upsilon Sun and served as Vice Illustrious Fellow of the Upsilon Sigma Phi in 1983. He is currently serving as Presiding Commissioner of the Third Division of the National Labor Relations Commission (NLRC) and writes a regular column for the Manila Standard.