Politics & Government

Filling the Unforgiving Minute: The Quiet Resolve of Kiko Pangilinan

The road to Sweet Spring Country Farm cuts through the heart of Alfonso, Cavite—past restless tricycles, fruit stalls, and the occasional rooster stubbornly crossing the road. It is a place far from the din of the Senate floor, and that’s precisely the point. Here, Francis “Kiko” Pangilinan—former senator, farmer, father, and Upsilon Sigma Phi Batch 1981—cultivates eggplants and advocacies with equal care.

For Kiko, Sweet Spring Country Farm isn’t just a hobby; it is a philosophy with roots. Located in Alfonso, Cavite, the all-organic farm is where he grows lettuce, coffee beans, coconuts, and more. It is also where he and his family harvest peace, away from the chaos of the political and showbiz world.

Where the Quiet Things Grow

In 2012, he bought a property in Alfonso, Cavite, which he now calls “Sweet Spring”—named after the rare natural spring on the land. Farming became personal for him after both of his daughters, Kakie and Miel, developed asthma. He wanted to make sure they had access to safe, chemical-free food grown right from their own land.

The farmhouse, built in 2014, was described by his wife, Sharon Cuneta-Pangilinan, as “homey.” Some of the furniture was brought over from their old home in Westgrove, adding to its warmth and familiarity. It had always been Ms. Sharon’s dream to have a farmhouse—and to see one built not just from wood and stone, but from dreams for the country, gives you a deeper glimpse into who Senator Kiko truly is.

He rarely speaks about it publicly, but beyond his growing affinity for farmers, a defining moment in his advocacy for agriculture came from his political career. In 2010, as the Liberal Party’s candidate for Senate President, Kiko ran against then-Senator Manny Villar, who was also positioning himself for a presidential bid. When Kiko lost, the only remaining committee chairmanship available to him was the Committee on Agriculture, Food, and Agrarian Reform—a post that few others wanted. But what began as a consolation assignment became his calling.

“By 2010 so umiikot na ako sa iba’t ibang farms, nakita ko na ‘yung mga problema. Sabi ko sa sarili ko…unless ako mismo ang magfa-farm hindi ko buong maiintindihan ‘yung mga dinadanas ng mga farmers,” he said.

That connection runs deeper than rooted vegetables. As the principal author of the Republic Act No. 11321 or the ‘Sagip Saka Act,’ Kiko advocates for direct government procurement from farmers and fisherfolk. “Middlemen drive prices up and incomes down,” he explains. “We were able to eliminate already the high prices of goods when we served as Food Security in PNoy’s administration, if Malacanang is willing to work with Congress, we can do it again.”

Still, the law’s implementation has been far from perfect. Many LGUs still rely on traditional procurement channels, and awareness among farmers remains low. Kiko remains vocal: “We crafted the law to protect and empower our farmers, but laws are only as strong as their execution. We need political will to fully bring Sagip Saka to life.”

His love for his country mirrors the care he gives to his family. To Kiko, farming is not just about food security; it’s about justice for our farmers. “I experienced firsthand what farmers go through, and it changed me. Their struggle became my fight,” he said.

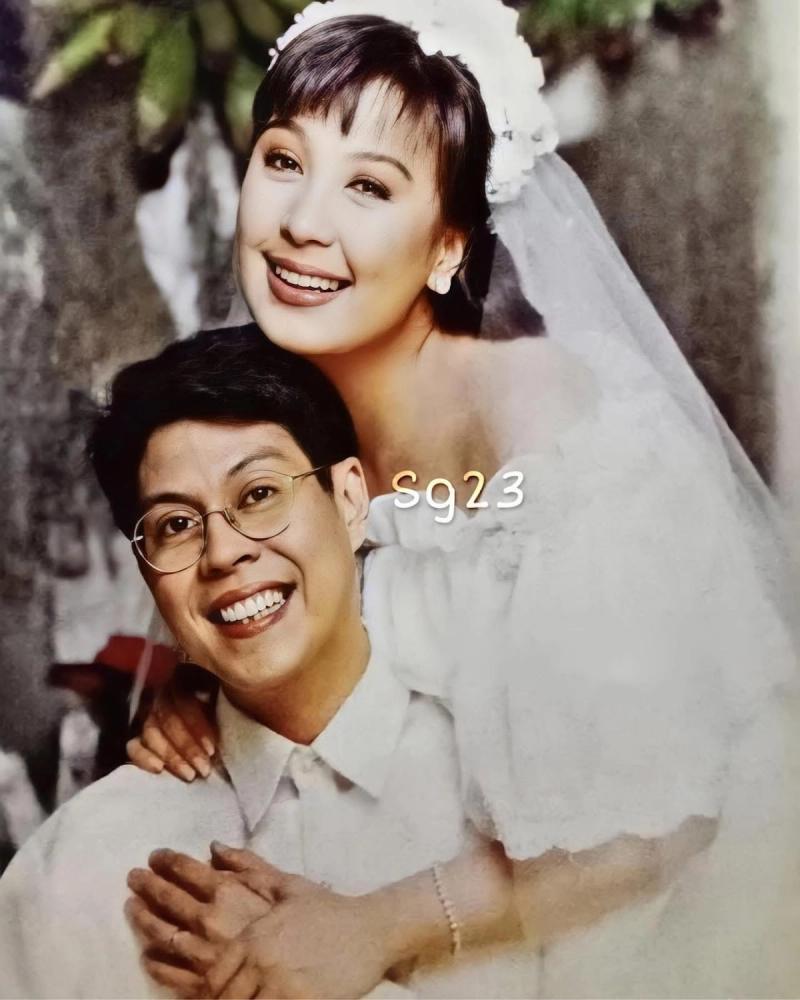

Love, As It Happens

Kiko and Sharon first met at the wedding of his younger brother, Anthony, to Maricel Laxa. Kiko, standing near the restroom, simply said “hello” when Sharon passed by. Later, Sharon would recall that she thought Kiko was a bit aloof—a little “suplado”—thinking he was playing hard to get.

Kiko is a devoted and honorable husband—but he’s not without his signature dad jokes. When asked about their dynamic as a couple, he often quips, “We’ve been together for almost 29 years. The secret? She does what she wants… and I do what she wants too.” He laughs and adds, “She goes her way, I go her way too. What’s hers is hers—and what’s mine is also hers.”

Together, they’ve raised four children: KC (Sharon’s daughter from a previous marriage) and their children, Frankie, Miel, and Miguel. His greatest fear? That one day, his children will ask what he did for the country—and he’ll have nothing to say.

A powerful reminder of his drive comes from Frankie (Kakie), who once said, “We must treat our farmers like our parents—because they’re the ones who feed us.” For Kiko, championing the rights of farmers is more than policy—it’s deeply personal. It’s part of securing a better for his children and future generations.

The Medicine Cabinet

After every meal, Kiko takes what he calls “pills.” They are not pharmaceuticals. They are small green chili peppers—siling labuyo.

“They lower my blood sugar,” he explains. “They turned my severe fatty liver into a mild one. And, well… they’re vasodilators,” he says, with a mischievous grin.

Among his staff, this practice has become a both a running joke and eventually an actual policy. During campaign sorties, someone is always assigned to secure a kilo of green chilies. It is just as important as preparing briefing notes.

The Public Servant with Dirt Under His Nails

Ask anyone who has worked with Kiko, and the same words surface: honorable and faithful. His wife, Sharon, once shared in an interview that Kiko would sometimes light candles while praying for their family, even shedding some tears in the process. This was taught to him by his mother, SDP Sister Emma Pangilinan, who showed him the importance of prayer in times of crossroads.

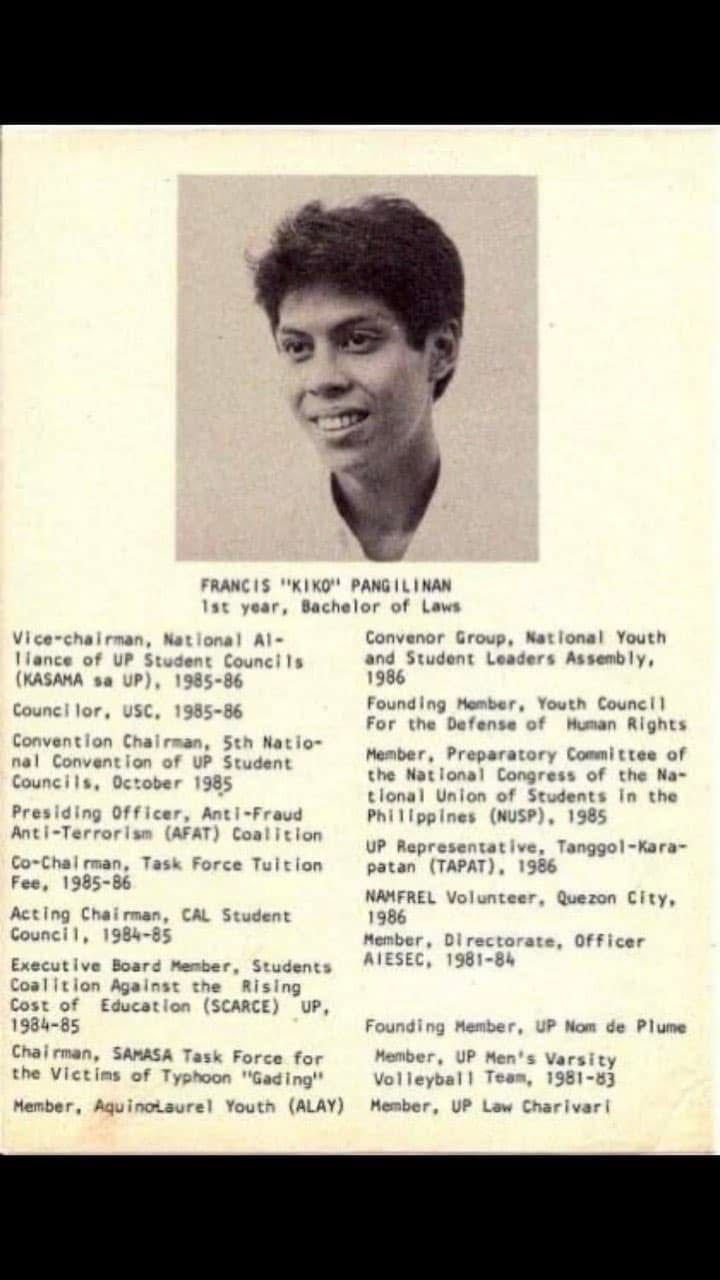

Kiko is also a man of intellect—his comparative literature degree from UP is evident in his eloquent and sincere speeches. His oldest brother, Joseph Pangilinan ‘79, shared that as a child, Kiko would fill their rooms with drawings and scribbles, always wanting to be a lawyer.

As a volunteer, and now as a staffer, I’ve seen Kiko’s humanity in ways most wouldn’t. He’s easily moved to tears. He’s been frail since childhood. He always needs lakatan bananas to keep his energy up on trips. He prefers printed briefers and writes in all caps. He prefers drinking water from the Summit brand, as advised by his doctors.

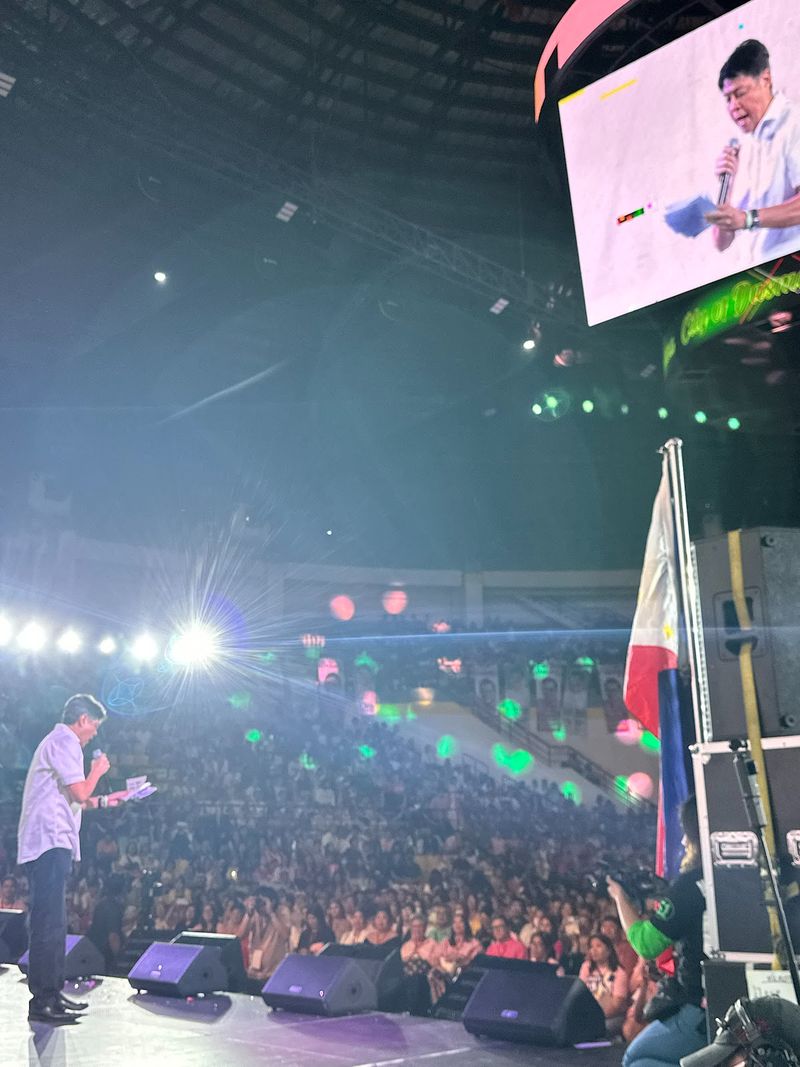

(Sen. Kiko in his 2025 Kick-Off Rally in Cavite)

But beyond the details, Kiko is—first and always—a father. He will put aside political ambitions when his wife or children call. He is honorable. He understands the weight of the causes he carries. He is a genuine public servant. I don't know how else to describe how much he loves his family, his country, and the farmers he continues to fight for.

Even in moments of political adversity, Kiko never forgets his faith. When the 2022 election surveys showed his struggle to break into the winning circle, he reminded his team:

“Good evening, everyone. We will do everything humanly possible, campaign our hardest to bring our message of food security, lower food prices, and good governance to our people. And in the end, we surrender to the Almighty, trusting that our people, capable of making informed decisions, will carry us to victory. Walang bibitiw. Tibayan ang hanay, gapiin ang kaaway.”

(Team Kiko’s Photo when we went to Batangas)

When he lost his bid for the Vice President in 2022, he didn’t spiral. He planted hope among our generation. He would often say that he has never seen an election with such energy from volunteers, especially the youth—and to him, the fight is far from over. “Hindi pa tayo tapos” he would always acclaim. Now, he’s at that point where he’s in one of his most gruesome battles in his political life—but he has always maintained the reverence, his leadership grounded in faith, showing unwavering integrity in the process.

“I will do my best and I will leave the rest to the people to decide. We will move heaven and earth to be able to win this. But in the end, you know, there are certain things that are not in your hands so you leave that to the people.”

The Observer Becomes the Voice

We rarely speak to him personally. We do this out of respect, to keep his mind clear for the demands ahead. But even in that distance, you feel how deeply present he is. You get to know him through the small things.

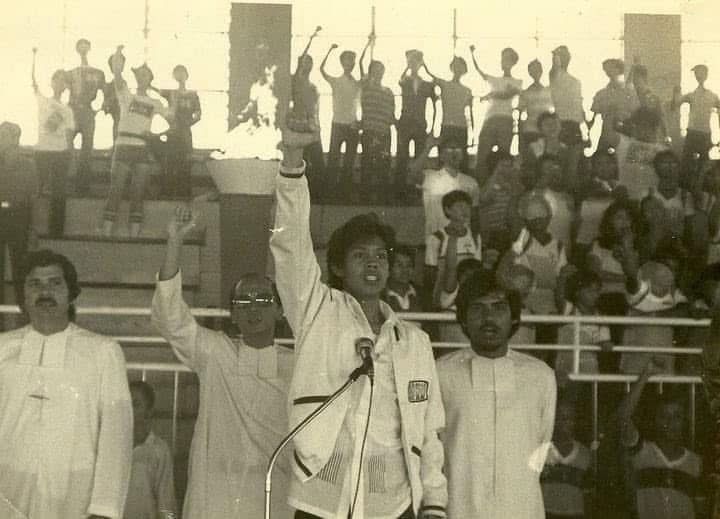

He entered UP as a freshman in 1981 after graduating from La Salle. That same year, he joined the fraternity. Back then, he would say he was apolitical, more focused on his hobbies like running and volleyball. But his path soon shifted toward politics, especially as he grappled with the fact that both Ninoy Aquino ’50 and Ferdinand Marcos Sr. ’37—once fraternity brothers—had become bitter enemies in the political arena.

“Bakit nangyayari ito? Mga fraternity brothers ko ‘yan ah,” he once said.

It was the events leading up to EDSA that ultimately drew him into a life of public service—one he has never left behind. His involvement in EDSA and the decisions he made as part of that movement are a testament to his character, always choosing what was right even when it was difficult.

He rose to the position of Senior Noble Fellow. He mentored younger brods and led by example. When a familiar name is mentioned today, he often says, “Nanang ako nyan,” with pride.

He consistently highlights how it was the fraternity—and his friends in SAMASA—that helped him become the first Student Regent of the UP System with actual voice in the Board of Regents.

(Kiko Pangilinan in his student Council days)

He’s introverted, quiet—but thoughtful. He never misses the chance to ask his staff to join him for a meal. He checks how people are getting home. He remembers birthdays. He asks, even in passing, how we’re doing.

Brother for Life, Mentor Forever

I started as a volunteer in 2022. Now, in 2025, I serve as one of his political officers. In those years, I’ve come to know Senior Brod Kiko Pangilinan ‘81 more deeply than I ever knew my own estranged father. He’s the reason I only ever applied to UP, why I became president of his youth arm, and why I chose to set aside my personal track in the university to help run his campaign.

His siblings adore him. They show up at sorties, pitch in at every campaign. His extended family—nicknamed Barangay Pangilinan—is a well-oiled team of volunteers who appear wherever needed.

(Photo of Barangay Pangilinan)

When I joined the fraternity, it was part of a 10-year plan: to help him win back a Senate seat. And now, we’re just a few knocks away from making that happen. To me, it’s always an honor to be part of history—and I know this journey is something I’ll carry and share for decades.

He is a man who inspires and humbles those who work with him. He is not my father. But he is the best father I never had.

That is why I believe that brod is thicker than blood.

And I have learned this: You do not fight for Kiko Pangilinan because he asks you to. You fight for him because he is already fighting for you.

About the Author

Lucas Buenaflor

Juan Lucas Antonio Buenaflor 2023 is the Executive Director of the Upsilon Sigma Phi Alumni Association, Inc. (USPAAI) for 2025-2027. A student leader, he has served in the UP School of Economics Student Council and as Chairperson of the University Freshie Council. At UP, he co-convened BUILD UP 2024 and held key roles in Diliman Games, the University Job Fair, Econ Week, and the National Youth Congress. As Fellow Orator, he leads the fraternity’s Special Projects Committee and spearheaded UpsilonCares - the residents’ flagship service program. Beyond UP, he is the President of Kilos Ko Youth and a Political Officer for Senator Francis N. Pangilinan ’81. He previously interned at the UNESCO Philippine National Commission under Secretary-General Ivan Henares ‘98. Before entering UP, he worked as an Account Executive Intern at BCD Pinpoint Direct Marketing, handling key accounts like UNICEF Philippines and DAVIES Philippines. An alumnus of the Kaya Natin! Movement and the Council of Asian Liberals and Democrats, he is also a recipient of the Gerry Roxas ‘46 Leadership Award. He is currently a second-year BS Economics student at the UP School of Economics.