Arts & Lifestyle

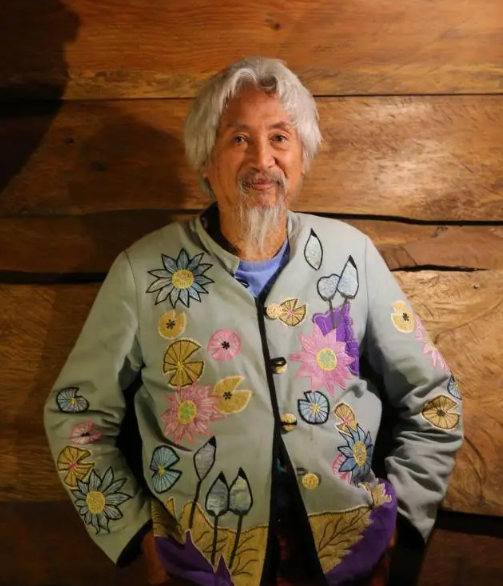

Kidlat Tahimik, 'indo-genius'

I always think of Baguio as more of a scent and a color rather than a place,” says National Artist for Film Kidlat Tahimik, who was born Eric de Guia 81 years ago in what is touted as the City of Pines. The pine scent, for one, means home to him.

Tahimik goes on recalling to Lifestyle in our interview, held at the cinematheque of his own Ili-Likha Wateringhole in Baguio, the time his younger brother, First Class Scout Victor de Guia Jr., died in an aircraft tragedy on July 28, 1963. De Guia Jr. and 23 other Filipino boy scouts were on their way to represent the country in the 11th World Jamboree in Marathon, Greece, when their plane crashed into the Arabian Sea near India.

The country’s “Father of Independent Cinema,” then 20 years old when the tragedy happened, remembers making the trip to India at the behest of his parents. He took the offer of the airline to go to the site “just to have the satisfaction” that a search was made for their family member. He went with the other representatives of the fallen boy scouts to the Bay of Bombay, where human remains were recovered, and later, to the morgue.

“It was tragic and painful, but I could keep my distance,” he says in reflection. “When we came back in Manila, there was a big ceremony at the Rizal Coliseum.” A year later, the City Council of Quezon City renamed streets in the Kamuning and Roxas Districts after the 24 scouts.

From Manila, Tahimik recounts, he took the trip to Baguio on a DC-3, a twin-engine monoplane, along with his brother’s coffin. He can’t forget smelling the pine trees as soon as the plane’s door opened, saying, “That was the first time I cried. Maybe the Baguioness of that thing connected me with my brother.”

Then he points out, “So that’s what I said of Baguio as a combination of the senses in my memory.” Baguio is also a place where contemporary American values and indigenous ways of living mix, and it was that kind of environment that helped him become the celebrated artist and multi-faceted person that he is now.

No script

“The cinematheque is a sudden idea, maybe like my films, no script,” he tells us one rainy August afternoon, speaking in a mix of Filipino and English. “I’ve always known that my films were not considered well enough to be examples of independent film. I allow whatever will happen, what the scenes would be, and where the story would go. It’s a kind of ‘Bathala na’ filmmaking.”

He then points out that Bathala na is different from the more known expression, “bahala na,” which connotes the colonial attitude of leaving everything to chance. Bathala na, he stresses, is a proactive attitude that has precolonial roots. After putting in the work, the final outcome is humbly left in the hands of the Higher Being.

Tahimik’s journey itself is a testament to the Bathala na way. He went from being a Baguio native, getting his first education under the American nuns at Maryknoll, to a student leader at the University of the Philippines (UP) in Diliman, to an MBA holder from the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School and eventually a maker of groundbreaking independent films, without attending any film school. His debut, 1977’s “Mababangong Bangungot (Perfumed Nightmare),” has earned accolades over the years. It took the 49th spot in the New Yorker magazine’s list of the greatest independent films of the 20th century that was released in April 2023.

“I don’t know how I made it,” he admits. “The thing lang is, ‘Wow, Charlie Chaplin’s ‘Gold Rush’ is on that list. Also Orson Welles, John Cassavetes, some of the French new wave cinema. Those people did their work and avoided a machinery like the producers, and they had artistic freedom to tell their story.”

Tahimik confesses, though, that while he got his National Artist award as a filmmaker, in 2018, he’d rather be known for being a little bit of everything else. He’s also an acclaimed installation artist, whose works has been showcased in many parts of the world. His recent National Museum large-scale work, “Indio-Genius: 500 Taon ng Labanang Kultural (1521-2021),” was first exhibited in Spain from October 2021 to March 2022. Last year, he had another installation that was shown at the São Paulo Biennial in Brazil.

Cosmic

Major parts of his “Indio-Genius” installation recently found a new home at the Mactan-Cebu International Airport, starting with two wooden sculptures depicting the historic voyage of Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan and his slave, Enrique de Malacca.

Tahimik explains that the term “indio-genius” stemmed from his mentor Lopez Nauyac’s mispronunciation of the word “indigenous.” He found the late Ifugao elder’s pronunciation “cosmic,” as it “combines the genius of the indigenous in one word,” and then incorporated the “indio” word that harks back to colonial times. He introduced the term when he was teaching at UP to instill pride among his young students.

“Although we became indios and we were colonized, the genius of the indigenous is still alive,” he says. “So why do we feel ashamed about it? Are we trying to be conformists to civilization? Just to be part of the trending culture? It’s not the question of this is more superior … We still have to assert our own in spite of these influences. That’s my battlecry now. I feel the youth can easily pick up indio-genius. It’s a catchword or concept that I think can work.”

He mentions Jose Rizal as an embodiment of the indio-genius, despite the national hero having studied abroad and practiced Western ways. “I have this statue at the National Museum show with Rizal in a bahag. When we think of Rizal, he’s always this guy in a winter coat. I want to show the youth his greatness lies underneath his overcoat. It’s a metaphoric picture, but still connected to our culture. Our ways of solving problems are in him, despite his outer Westernization.”

Tahimik says he has started slowing down with work to focus on taking care of himself, saying, “My wife and children got angry that I still did that Brazil project … I had to slow down. I can focus on a little bit of helping the young people reassess the role of culture without being academic.”